A good time to plant bushes, trees and perennial flowers is during fall.

By: Bart Ziegler: From The Wall Street Journal Online

Autumn also is a good time to shop for these plants, since garden centers and big-box stores usually have them on sale, often at ridiculously low prices.

One autumn day three years ago, I spotted two sorry-looking shrubs at the local garden center. Though they resembled a few bare sticks stuck in a pot they were only $12 each - about a third of their original price. I'm a sucker for a bargain so I decided to take a chance on them.

As an early November snowfall swirled around me, I chopped through the crusty surface of the soil and planted these Charlie Brown viburnums in my front yard, all the time thinking how I might have to pull out their dead carcasses six months later.

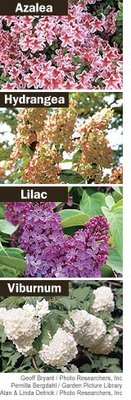

But in the spring, crinkly green leaves unfolded along their branches, then a sprinkling of white flowers. The shrubs grew and grew and by this past spring they had turned into stately beauties, each about 5 feet high and 7 feet wide. Row upon row of stunning, snowy blossoms covered their branches in June, followed by colorful berries the birds loved.

My happy experience with these viburnums wasn't a fluke. It turns out that many shrubs, trees and perennial flowers can be planted in the fall. "Fall planting is far underappreciated by folks," says Patrick Callina, vice president of horticulture at Brooklyn Botanic Garden in New York.

And as I discovered, autumn also is a good time to shop for these plants, because garden centers and big-box stores such as Wal-Mart, Home Depot and Lowe's usually have them on sale, often at ridiculously low prices, to clean out their inventory.

Mail-order supplier Wayside Gardens has cut the price of an unusual hydrangea introduced nationally this year, called "Lady in Red," by 20%, to $19.95; its frilly flowers mature from a pinkish-white to a deep crimson, while its leaves turn a reddish-purple in autumn. Lowe's stores in the mid-Atlantic region are selling three-gallon containers of low-growing parsoni juniper shrubs for just $7.98. Many local plant stores also have slashed prices; Ward's Nursery & Garden Center in Great Barrington, Mass., has marked down all its shrubs and trees by 20% to 50%. Bargains also can be found on eBay: Pase Greenhouses in North Collin, N.Y., was offering northern bayberry bushes for $2.99.

Why can shrubs and other hardy plants safely be put in the ground when nature seems to be saying that it's time to hang up your shovels for the season? The chief reason is that while the air may be nippy, the soil stays warm for many more weeks.

"Although the top of the plant may have lost its leaves, the roots can continue to grow until the soil temperature approaches freezing, which is much later than when the air temperature approaches freezing," says Marvin Pritts, chairman of the Horticultural Sciences Department at Cornell University. In warmer parts of the country where the ground doesn't freeze the roots can establish themselves all winter. Ironically, spring isn't always the optimal time to plant, because the soil typically remains much colder than the air for many weeks, in a reversal of autumn's effect. Plus, the warm days then may stress the newly transplanted shrub, flower or tree.

Autumn also tends to see more rain than the summer months, giving another boost to your fledgling plants. The cooler days are also easier on them than hot summer weather - as well as being much more comfortable for you to be outside digging holes.

Come the first mild days next year, your new plant will be ready to burst into leaf and bloom, benefiting from its head start over anything you would put into the ground in spring.

Not everything is suitable for fall planting. Some experts say that oaks, firs, willows, hemlocks, magnolias and rhododendrons are more safely planted in spring, but other authorities disagree. (Ask your local garden center for advice because this list varies by region.)

And shrubs and perennial flowers that are sold in "bare root" form - meaning the roots aren't planted in a pot but instead are soil-less and covered by plastic wrap or wax - also are better off planted in spring. They may take longer to become established in your yard than plants that were growing in soil and as a result may not grow new roots by the time the ground freezes.

Plant your new shrub or tree by digging a hole that's about twice as wide and about as deep as the container or burlap bag it came in. If the plant was in a pot, whack the sides of the container with a trowel to loosen the roots, then tip the pot on its side and gently pull out the plant by holding its trunk.

If the roots are wound around each other, loosen them by pulling them apart or, in severe cases, cutting some of them. (I roughen up the roots by running a gloved hand repeatedly over them.) Rootbound plants are common in fall, because they may have been sitting at the garden center all summer. If you don't loosen the roots, they may continue to twist around one another and stunt the plant's growth.

Add a bit of peat moss or humus (both available at garden stores) to the soil to help it retain moisture, then pack it loosely around the roots. Make sure the plant's root ball is about level with the surrounding earth, not lower. Then give your plant a good drink of water.

After planting, many experts advise spreading a layer of mulch, such as chipped wood or bark, around your new plant to help moderate the fluctuations in soil temperature, especially in areas where there's not likely to be snow cover to perform that function.

"The biggest risk from fall planting is a rapid drop in temperature," says Cornell's Mr. Pritts. "If the soil freezes before the roots become established, then plants can heave out of the ground during the freezing and thawing cycles of winter." But be careful not to let the mulch touch the plant's stem or trunk. Wet mulch can lead to growth of microorganisms that could rot the plant, warns Mr. Callina of Brooklyn Botanic Garden.

So take a chance with fall gardening. Next spring you'll be glad you did.

Email your comments to rjeditor@dowjones.com

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

With the latest news and trends in the Real Estate Market

ABOUT

Links

ADD VF CONSULTING REAL ESTATE BLOG TO YOUR FAVORITES!

Blog Archive

-

▼

2005

(522)

-

▼

October

(68)

- Blueprint for Buying - or Renting: Timing for a Ma...

- New "Price Bloat" Index Pinpoints Overvalued and U...

- Six home buyer mistakes to avoid

- Give Shrubs a Head Start and Save Some Cash in the...

- Real estate sales to hold strong in 2006

- Gas heater a great addition for garage or shop

- More people In Their 20s Seek Homeownership

- Buyers Need Real Estate Professionals in the Inter...

- The Weekend Guide! October 27 - October 31, 2005

- Economic future bright through 2007, bankers' grou...

- Younger Buyers Flood the Home Market

- C.A.R. reports median home price increased 17.3 pe...

- California real estate values don't disappoint

- Homeowners Keep First Homes, Buy Second

- Home Sellers Remain Optimistic

- Housing Poised to Recede from Peak Levels

- Tax Reform Panel Makes it Official: No More Home E...

- Risk of home-price declines rise

- How real estate can save on your income taxes

- Hispanic Homeownership on the Rise

- How to paint knotty pine and concrete

- Real Estate Bubble: A Self-Fulfilling Prophecy?

- The Weekend Guide! October 20 - October 23, 2005

- Investors Flipping Over Second Homes

- The Riskiest Housing Markets: A Drop in Home Price...

- Can vacation home qualify for a tax-deferred excha...

- Pricing home to sell in a changing real estate market

- Homebuying Varies for Hispanic Households

- SoCal real estate sales, prices up since last year

- Real estate's October report card

- RealEstate.com Survey Polls Home Sellers and Real ...

- Time to prepare for those high winter energy bills

- Can hot market lessen real estate agent's value?

- Best way to renovate bathroom floor

- Diary of a real estate flipper

- The Weekend Guide! October 13 - October 16, 2005

- Real estate sales on record pace this year

- The end of multiple offers

- More Young Adults Become Homeowners

- Housing inventory grows in some major markets

- Real estate buyers fall victim to 'offer shopping'

- Perfect home, perfect staging, imperfect market

- Housing Counsel: Swapping Properties - What is "Li...

- Interior designers reshape real estate buying

- Cost recovery questioned in bathroom remodel

- Solid subfloors make for happy feet

- New tax law irks couple in real estate exchange

- Pitfalls of kitchen remodeling revealed

- First-timers find a place to call home

- Study Identifies Flipping's Sweet Spot

- California Home Prices May Be Moderating

- Demand Drives Pending Home Sales to New Record

- The Weekend Guide! October 6 - October 9, 2005

- Housing Prices Slow in Hot Markets

- Check Your Insurance Policy

- National Foreclosures Decrease 4.3% in August: Rea...

- No more 60-day notice to Terminate Tenancy

- Energy Department Will Enforce New Air Conditioner...

- 10 Tips for Selling in the Fall

- Real estate listings inventories rising

- Is the Housing Boom Headed For a Soft Landing or a...

- Boost for Consumers With Low Credit Scores

- Pros and cons of owning rental real estate

- Small-scale model helps see the skylight

- Residential Environmental Hazards Guide has been R...

- New HVAC Duct Sealing Requirement for Property Owners

- New Tools Available To Hedge Your Home

- Soundproofing house walls

-

▼

October

(68)