By: Robert Guy Matthews: The Wall Street Journal Online

One suggestion from President Bush's tax-reform advisory panel - restricting the deduction for mortgage interest - raises the question: How far should the U.S. government go in encouraging homeownership?

President Bush's tax-reform advisory panel today will urge significant changes in how American households and businesses are taxed. But one of its recommendations - restricting the deduction for mortgage interest - already is making headlines and drawing political fire.

The suggestion calls attention to a debate among academics and policy wonks: How far should the U.S. government go in encouraging homeownership? Does the U.S. tax code's tilt toward homeowners cause Americans to overinvest in housing? Would changing the tax code bring down home prices?

This is just one issue in the report that the nine-member, bipartisan commission is expected to approve today. The panel backs two alternatives to the tax code: a streamlined version of the current income tax and a revamped tax strategy designed to encourage more saving and investment. Neither is likely to become law as proposed, but they will frame a debate likely to go on for years.

Both options curtail the current tax break for homeowners that allows Americans who itemize their deductions to deduct interest on mortgages of as much as $1 million. The deduction is worth more to upper-income taxpayers: $10,000 in interest deductions cuts the tax bill by $3,333 for someone in the 33% bracket, but $1,500 in the 15% bracket.

The panel suggests turning the deduction into a tax credit equal to 15% of eligible mortgage interest, which means the tax break for interest on a $100,000 mortgage would be the same for every taxpayer, regardless of income. It suggests lowering the $1 million ceiling to the size of an average mortgage, using Federal Housing Administration regional data.

In today's real-estate market, the ceiling would range from $172,632 in rural areas to $312,895 in the urban corridors of New York City, Boston, Washington, D.C., and parts of California. The FHA says about 81% of its loans are close to the lower end and about 2.5% of loans are in the ceiling range.

The change would mostly affect only taxpayers in higher brackets with above-average mortgages. Under current interest-deduction rules, a taxpayer in the 35% income bracket with a $500,000 mortgage at 6% in the country's pricier urban corridors can reduce his or her taxes by just over $10,000. By contrast, under the new proposal, that same individual could claim a credit of roughly $2,800, according to Goldman Sachs.

The commission also recommends ending tax breaks for second homes and home-equity loans. In its proposal, current homeowners would be able to keep their original mortgage-interest deductions, which would change only if the homeowners refinanced or purchased a new home.

The panel didn't wipe out the tax deduction for housing altogether as it did the deduction for state and local taxes. President Bush, in appointing the panel, asked members to "recognize the importance of homeownership."

"We were relieved of the philosophical question of whether homeowner preferences should be in the tax code," said Charles Rossotti, a former IRS commissioner and one of the architects of the mortgage-interest proposal. The goal, he said, was to "make sure that it is still possible to own a home," but to reduce the size of the tax break for housing - giving the panel the money it needed to fix other parts of the tax code - and to restructure it so the break isn't so tilted in favor of high-income taxpayers.

Nevertheless, the housing industry was quick to criticize the proposal. "The tax deductibility of interest paid on mortgages is both a powerful incentive for homeownership and one of the simplest provisions in the tax code," said Al Mansell, president of the National Association of Realtors. "It should not be targeted for change."

The association warned that the plan would push down prices of homes, especially upper-end ones. Homebuilders and mortgage bankers sounded similar alerts, as did some think-tank economists. The proposed change "would have a negative impact on the home-building industry," says economist Adam Carasso of the Urban Institute, a think tank in Washington.

Admirers of the proposal say curtailing the tax code's tilt toward housing is in the nation's long-term economic interest because it might divert savings to other parts of the economy, and that any downward pressure on home prices caused by the tax change would be modest and manageable. Backers also say that it is wise to restructure the tax break so it doesn't benefit higher-income taxpayers as much.

Richard K. Green, a tax economist at George Washington University, calls the proposal "conceptually...really a good idea," and says the panel wisely focuses the tax break for homeownership on families who might otherwise not be able to afford to buy a house.

Other economists question the industry's assertion that watering down the housing-tax break would reduce homeownership. About 68.6% of Americans own their homes, according to the Census Bureau. Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom don't have such tax breaks but have similar levels of homeownership.

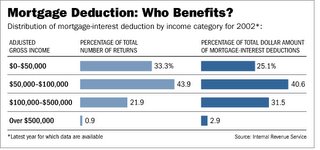

In its deliberations, the tax panel looked at who benefits from the current mortgage-interest deduction. Their answer: Mostly higher-income earners who itemize deductions on their tax returns rather than taking the standard deduction. Two-thirds of taxpayers don't itemize, the Internal Revenue Service says.

And, the IRS says, about 35% of the tax savings from the mortgage-interest deduction goes to taxpayers with gross annual incomes above $100,000. In the U.S., 9% of taxpayers earn more than $100,000.

But the politics of reducing this popular tax break, even as part of a broader tax overhaul, are tough. Sen. Max Baucus of Montana, senior Democrat on the Senate Finance Committee, said the mortgage-interest cap wouldn't get through Congress. In the 1990s, caps on mortgage interest were considered but quickly dropped because they were politically unpopular.

Even Mr. Rossotti acknowledges that the mortgage-interest cap has a slim chance of success. But he argues that Americans don't benefit as much from this deduction as they think; the tax break for mortgage interest is offset by factors that boost the taxes of those who take advantage of it.

"It is one of the great deceptions in the tax code," Mr. Rossotti said. "I defy anyone to try to figure out the interaction between what you get after phase-outs of the personal exemption, phase-outs of the itemized deductions, how much is taken back because of the alternative minimum tax and state and local taxes."

Email your comments to rjeditor@dowjones.com.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

With the latest news and trends in the Real Estate Market

ABOUT

Links

ADD VF CONSULTING REAL ESTATE BLOG TO YOUR FAVORITES!

Blog Archive

-

▼

2005

(522)

-

▼

November

(54)

- How to earn up to $250,000 tax-free every 24 months

- Home additions that stand the test of time

- Is Your Building Going Condo? Here's What You Shou...

- Will refinance lessen homeowner's real estate tax ...

- Doors make a good first impression

- How does FICO score impact real estate refinance?

- Happy Thanksgiving!

- Real estate excluded from living trust causes trouble

- Building permits pay off for sellers

- Overpricing can be risky for real estate sale

- Mortgage shopping: what you should know before you...

- Condos Go Cabanas: Developers Sell Poolside Huts a...

- Pros and cons of 'flipping' real estate

- Fast real estate profits require elbow grease

- Ten Fall Maintenance Tips

- Holidays Coming? So Are the Most Serious Homebuyers

- The Weekend Guide! November 17 - November 20, 2005

- State Existing-Home Sales Hit Another Record in 3Q

- NAR: Home Appreciation Still Hot in Most Areas

- Why traditional real estate brokerage is alive and...

- SoCal real estate sales climb for third month

- Seniors flock online to find homes, survey says

- C.A.R.'s Housing Market Forecast for 2006

- Housing Market Shows Further Signs of Cooling

- Financing the Luxury Purchase

- Housing group to present study on real estate affo...

- New Program to Help Homeowners Refinance with FICO...

- Real estate affordability sours Californians

- Remodelers Promote Aging-In-Place Features in Exis...

- Real estate industry fights to preserve real estat...

- Should You Remodel or Move?

- The Weekend Guide! November 10 - November 13, 2005

- Don't Let Housing's Seasons Scare You

- The Ups and Downs of Flipping Condos for Fast Cash

- Real estate purchases jump

- What's Really Happening with Home Prices?

- Will Your Condo Retain Its Value? Five Tips for Ed...

- Join the Game, But Know the Real Estate Investing ...

- Forget About Housing Boom or Bubble

- How to prevent home seller's remorse

- Single-family homes best spot to sink money

- Panel revises real estate loan interest tax writeoff

- Realty Q&A: Has the Market For Real Estate Run its...

- Investors say housing market overvalued

- Reducing Tax Deductions Could Hit Property Values

- Real estate inheritors learn value of living trusts

- Pending Home Sales Index Close to Record

- Is It Time to Remodel The Homeowner Tax Break?

- The Weekend Guide! November 3 - November 6, 2005

- Shopping for a Home in Winter: A Strategy for Barg...

- C.A.R. says proposed change to deductibility of mo...

- Times have changed for real estate

- 7 Home Repairs You Can't Ignore

- Realtors go to bat against expected real estate ta...

-

▼

November

(54)